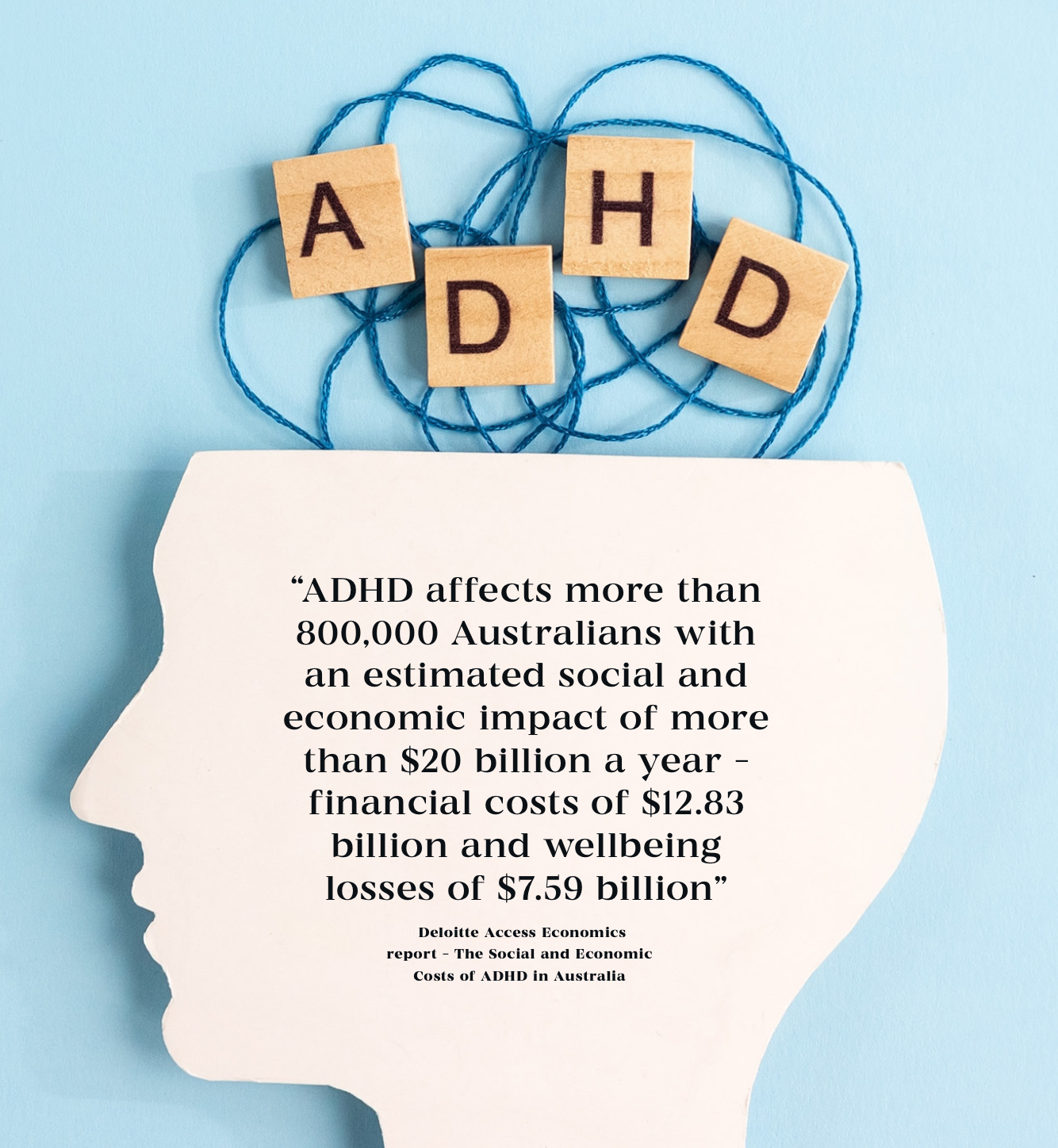

Spotlight on ADHD

By Rebekah Devlin

Once dismissed as a behavioural issue affecting young boys, ADHD is becoming part of the national conversation. But there are still so many misconceptions about the neurodivergent brain and the need for support, says Dr Beth Johnson.

What is ADHD?

ADHD is a neurodevelopmental condition that arises in childhood (i.e. is apparent before 12 years of age), which results in brain development and brain activity that is marked by attention differences, self-control and impulsivity. Although it is highly heritable and genetically linked, it’s diagnosed according to behavioural symptoms of hyperactivity and impulsivity. The predominant presentation of ADHD is combined type, that is, where people presents with both hyperactive and inattentive symptoms. However, there are two other subtypes, which is ADHD – hyperactive type, and ADHD – inattentive type. It persists into adulthood in 80 per cent of cases and can affect a child at school, at home, in friendships, work and relationships.

Who can diagnose ADHD?

In childhood, a paediatrician or child and adolescent psychiatrist can diagnose (may be supported by assessment from a psychologist). In adulthood, either a psychiatrist or psychologist can diagnose.

Stimulant medications get a bad rap. Is this fair? How do they work and what is their benefit?

Our brains and nervous system are made of cells, called neurons. Neurons communicate with each other by releasing chemicals, called neurotransmitters, which pass between the neurons via synapses (the small gaps between neurons). The neurotransmitter is taken up into the next neuron by attaching to a receptor, kind of like a key (the neurotransmitter) and a lock (the receptor). Once neurotransmitters are released, any excess is reabsorbed by the neurons.

Dopamine is a neurotransmitter that helps to regulate attention, executive function and movement. It is thought that in individuals with ADHD, the dopamine systems are affected: e.g. dopamine might be produced in lower amounts, the receptors don’t bind dopamine so well, or dopamine is reabsorbed too quickly. Stimulants work by making dopamine available at the synapse for a longer period of time (slows reabsorption of dopamine). It’s important to note that stimulant medication, and other ADHD medications don’t cure ADHD, they just reduce symptoms.

Stimulants are an effective support for many individuals with ADHD, their tolerability has been evaluated for several decades. They’re non-addictive, relatively short acting (12 hours), and the impacts of the stimulants can be seen rapidly (within hours to days). If tolerability is poor, then it’s safe to withdraw.. Also, the impacts of non-treatment must also be balanced, where adolescents or adults may self- medicate through alcohol, addictive stimulants (ice, meth, cocaine) or cigarettes/nicotine.

Children with ADHD are often labelled as “naughty”. What kind of impacts can this have on their mental health and self-esteem?

Poor academic achievement, social rejection and isolation, has a cyclic impact (the more they are socially excluded and rejected, the fewer opportunities they have for building positive and sustaining relationships… and so it cycles), which can progress to development of anti-social behaviour, anxiety, perfectionism, withdrawal.

What can schools do to create a more inclusive, understanding and engaging learning environment for neurodivergent kids?

Firstly, education for neurodivergent kids and how it presents in the classroom is key — that these kids aren’t interrupting or fidgeting because they want to be naughty or to intentionally cause trouble.

They can’t help being distracted by the sounds outside. They’re not being intentionally lazy, attention seeking, manipulative or pushy. The work of Ross Greene (author of The Explosive Child and Lost at School) and programs like the Westmeade Feelings Program have really helped to break down stigmas and help teachers identify the specific lagging skills that children might be experiencing. Examples of lagging skills might be flexibility/adaptability, tolerance for frustration, approaching something new, problem solving. By understanding that the behaviour is an outcome of an underlying skill that the child lacks, breaking down the skill to help them learn and solve the problems, and working collaboratively with the child to help them identify their feelings and identify when struggles routinely occur and how to best help during those times, we can begin to develop a tailored approach for neurodivergent kids.

ADHD has been gaining media attention recently thanks to people like Em Rusciano. How important are these role models in breaking down stereotypes?

It’s such a relief to see, particularly as a pathway to self-compassion and help seeking. Regardless of the number of people who actually go on to receive an ADHD diagnosis, it’s so heartening to see these difficulties as just another part of the human condition, just like we view anxiety or depression, and that these are things that we can seek help for when they begin to impact on our daily functioning and relationships.

Dr Beth Johnson is Lead Investigator: Monash Autism/ADHD Genetics and Neurodevelopment (MAGNET) project, Turner Institute for Brain and Mental Health.

Read more on the characteristic of ADHD here.