Inclusive children: inclusive schools

By Erin Buie

Inclusion is the latest buzzword being flung around by the government, schools, teachers and parents. But what does it really mean? Ask a five-year old and it’s simple, inclusion means including everyone.

But unfortunately, it’s not quite that simple. So, what does inclusion really mean in practice? How can we make inclusion a reality in schools and society? Is an inclusive society even achievable?

Misa Alexander is a mother of three boys and co-founder of Fergus & Delilah, a not for profit organisation focused on helping children belong. She thought she had crossed all the ‘Ts’ and dotted her ‘Is’ before sending her middle son, who is autistic, to her local preschool. She had met with the teachers and discussed inclusion; how to make the environment more conducive to Hugo’s sensory needs, how to make the curriculum more accessible and how to communicate in sign language to assist Hugo’s speech.

As far as she could see Hugo was stepping into an ‘inclusive’ schooling environment.

But it didn’t take long to discover that Hugo was having trouble making friends. Quite simply, Hugo was not being ‘included’ by his peers.

The gap between Hugo and the other children was just too big.

So why, during a time where ‘inclusion’ is a hot topic at most school staff meetings, are children struggling to belong?

This question can best be answered by looking at a philosophy of human development constructed nearly 80 years ago. In 1943 Abraham Maslow outlined the progression of human needs in his paper “A Theory of Human Motivation” in the Psychological Review.

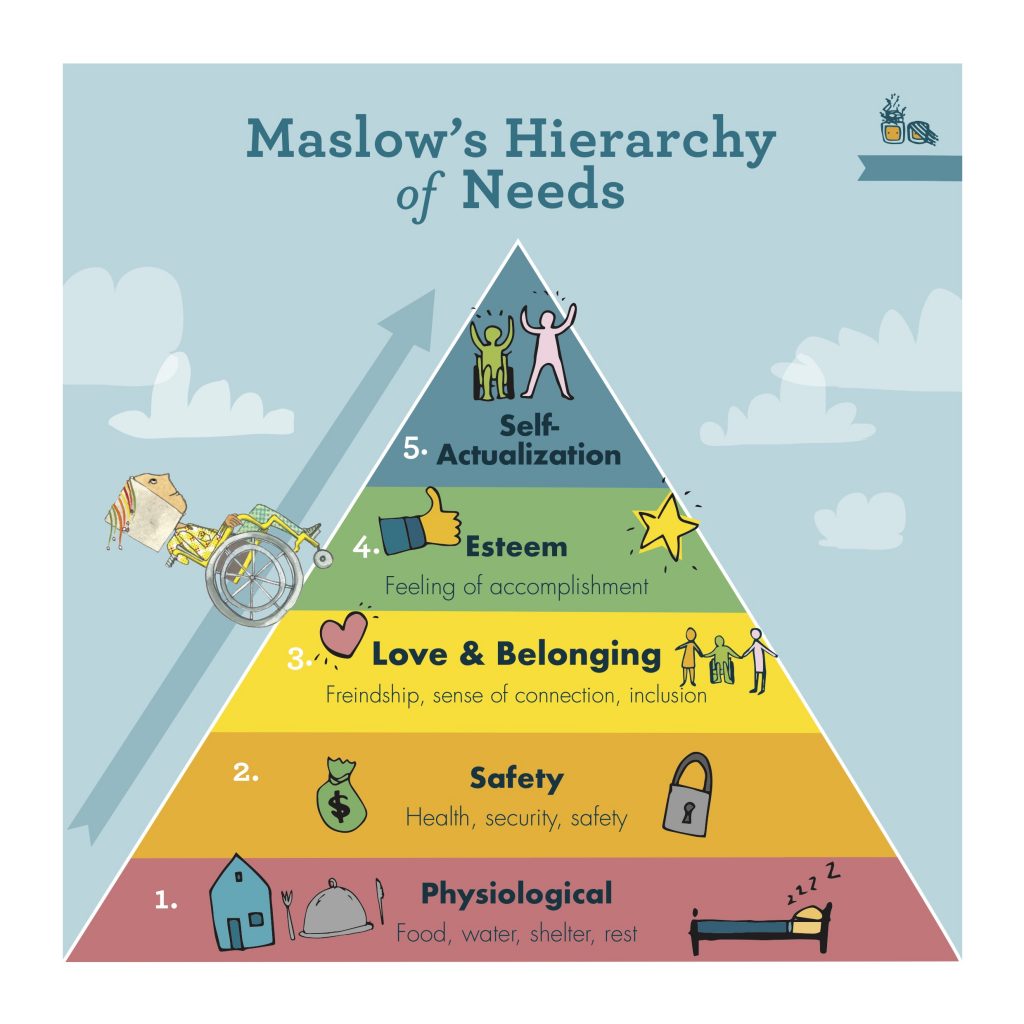

He explained how people’s needs begin with physiological (food, water, warmth), then progress up through to safety, to belonging and love, to esteem and finally to the pinnacle; self-actualisation. Needs lower down on the hierarchy must first be fulfilled before progressing up higher.

Maslow’s Hierachy of Needs is still widely regarded and routinely referred to by psychologists and forms an integral part of teacher training at university.

So, what does this have to do with inclusion? Inclusion is synonymous with belonging and love. The third step on the ladder. All schools have a legal responsibility to ensure the needs in step one and two are met but the school’s obligations to satisfy the needs of step three become blurry.

And yet, according to Maslow we cannot expect students to grow as individuals if they do not first feel a sense of belonging amongst their peers.

The New South Wales government just brought out their latest objectives for a Disability Strategy in schools including; strengthen support, increase recourses and flexibility, improve the family experience and lastly, track outcomes (2019, https://education.nsw.gov.au). But they too have forgotten the importance of the third tier on the hierarchy. Children feeling included. How can schools go beyond meeting basic human needs and ensure all children belong?

Misa and Erin Buie, a writer and special needs teacher found an answer to this question using a different approach to inclusion. An approach that focuses on fostering inclusive attitudes in children. A child cannot belong in an environment that does not accept him/her for who s/he is. For belonging and inclusion to truly exist; children must be taught how to be inclusive of each other.

We teach young children how to share, how to be polite, and how to take turns but we do not explicitly teach children how to embrace each other’s differences. The result, children like to stare at people who are different. And stare and stare and stare until an adult tells them to stop staring at which point they walk away. So how can we teach children to stop staring and start interacting with each other’s differences?

Lev Vygotsky was a great education philosopher who created the Zone of Proximal Development (1978) to explain how children can learn complex concepts. The Zone of Proximal Development is founded on the idea that people can only learn new information if it is based off their prior experiences and they are supported to make these new connections by a person with the appropriate knowledge and skills.

When the gap between a child’s own experiences and the new concept is too large then the new concept is unattainable.

This explains why children will stand frozen, glued to the ground, relentlessly staring at someone who appears very different to themselves. They simply do not know how to move past staring because their differences are too far from their norm to make a connection with.

It is the role of the adult, as the person with the appropriate knowledge and skills, to support the child to bridge the gap between themselves and the person they are staring at. Instead of teaching our children to ‘stop staring’ we should be teaching them to smile and say hello. Staring is a good thing. It means the child is interested in that other person. Let’s not squash that interest, let’s build off it and welcome the experience.

When Misa saw the children in the playground staring at her son she recognised that they were in need of a little guidance in how to interact with Hugo. So, she made up a flier for them to take home to read with their parents. The flier introduced Hugo; his likes and dislikes, some of his autistic characteristics, and what makes him smile.

Misa noticed a change at school. The students started saying ‘hello’ to Hugo. They started playing together, hugging Hugo goodbye at the end of the day. Misa’s flier had helped support the children to make the step past staring to interacting and Hugo was now belonging.

The lack of understanding and acceptance of differences is not a problem isolated to mainstream schooling; exclusion and segregation can be a part of any school environment if the students are not taught how to be inclusive of each other.

After the success of Misa’s flier she realised that she wanted to help more children learn how to be inclusive of differences. Misa teamed up with Erin and together they published Fergus & Delilah, a children’s book aimed at the neuro-typical child that explores disabilities and differences. A book specifically designed to teach children how to be inclusive. They have sold over 2000 books, largely to preschool and primary school teachers who have been desperately searching for inclusion resources.

Misa and Erin are now implementing an inclusion pilot program for early primary school students, which uses a range of highly engaging learning activities and resources to explicitly teach children how to be inclusive.

The feedback has been overwhelming.

So now when Misa is asked what does an inclusive school environment mean to her she replies; yes, there needs to be ramps and other access facilities and calming spaces, yes the curriculum needs to be adapted suitably, yes basic needs must be met but it must also be a place where every child feels accepted by their peers, so that every child has the opportunity to thrive.

If the next generation learns how to be inclusive from a young age than they will grow up to be inclusive employers and co-workers; creating an inclusive society where everyone can belong.

For more information about Fergus & Delilah or to purchase a book, please visit fergus-delilah.com