A guide to: being a friend in the playground

By Dr Susan Lowe

Figuring out how to be a learner in the classroom can be challenging, but problem solving how to be a friend in the playground can be even harder work for many children.

WHAT DO WE KNOW ABOUT EFFECTIVE WAYS TO HELP OUR CHILDREN?

In 2017, a comprehensive review by O’Connor and colleagues of evidence-based approaches which were associated with successful outcomes for social and emotional learning identified 4 core principles.

• Sequence a range of activities in a logical order

• Embed these activities in active, dynamic learning which provides children with opportunity to practice friendship in a real-life context

• Focus on one aspect of friendship at a time

• Teach a specific skill, rather than general skills

Learning to be a friend requires cognition. Social cognition, required for interactions with other children, is the ability to attend to what is happening in the playground; the ability to remember expected social behaviours; and then to plan and problem solve; and finally execute these behaviours in specific interactions and games, self-regulating thoughts, feelings and actions. Researchers are now exploring how ‘soft’ skills such as these may impact positively on both academic tasks and social interactions.

HOW CAN WE SUPPORT CHILDREN IN LEARNING TO BE A FRIEND?

We can teach children cognitive strategies. These are the thinking tactics children need in the ‘here and now’ to match their interaction with another child and the game being played.

What thinking strategies for attending does a child need in order to be a friend? A child needs to notice, by using his/her senses, to look and listen to what the other children are saying and doing; to have a ’just right’ level of arousal and alertness (i.e. not be sensory overwhelmed by all the noise and movement); to stay focussed and not wander off; to switch attention between banter of friends and the skill required for the game;

What thinking strategies for remembering does a child need in order to be a friend?

A child needs to remember where to go to find a class mate; remember how to join in; remember rules of games (e.g. bowler has 10 throws then we switch to a different bowler) and remember facts (e.g. everyone gets ‘out’ sometimes)

What thinking strategies for planning does a child need in order to be a friend?

A child needs to know the goal of a game; identify obstacles (e.g. getting ‘out’ meant that the ball was out, not that the kids hate me); anticipate (e.g. what might happen if I lose my temper?); problem solve (e.g. what if I can’t find my friend?).

WHAT DOES THIS LOOK LIKE IN PRACTICE?

We identify which specific cognitive strategies a child is struggling to use by observing the child with friends in the playground. For example, Peter wants to join in the chasing game but he is not listening to the rules the other children have made up for today’s game. His mind is focussed only on one thing: being ‘in’. He starts running and tagging without remembering how to join the game. He doesn’t know today’s game plan which is to tag 3 kids then switch to a different tagger.

We sequence a number of specific strategies which we want to teach Peter, embed these strategies in fun playground activities, teaching one strategy at a time.

WHAT MIGHT EXPLICIT TEACHING OF A SPECIFIC COGNITIVE STRATEGY LOOK LIKE?

- Modelling (my turn your turn) so that Peter can imitate you

- Task analysis, breaking the teaching down into small essential steps

- Verbal prompt e.g. What do you do first? Next? After that?

- Specific verbal praise for a desired action e.g. Great stopping before you stormed into the game! You looked then listened to figure out how to play. I’m proud of you stopping.

- Practice! Practice!

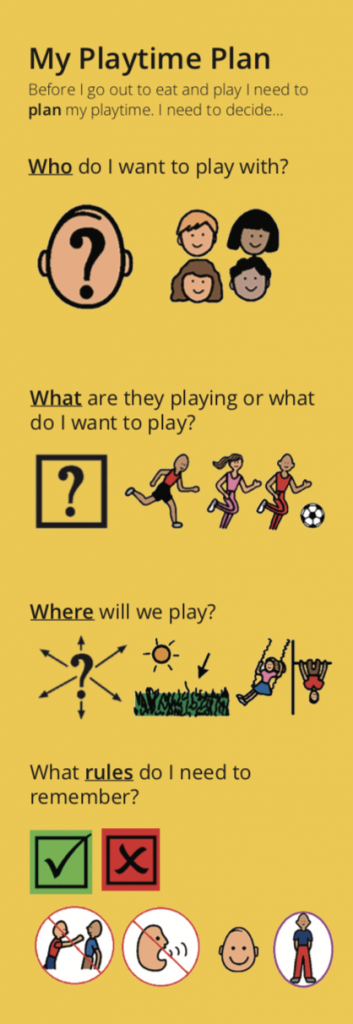

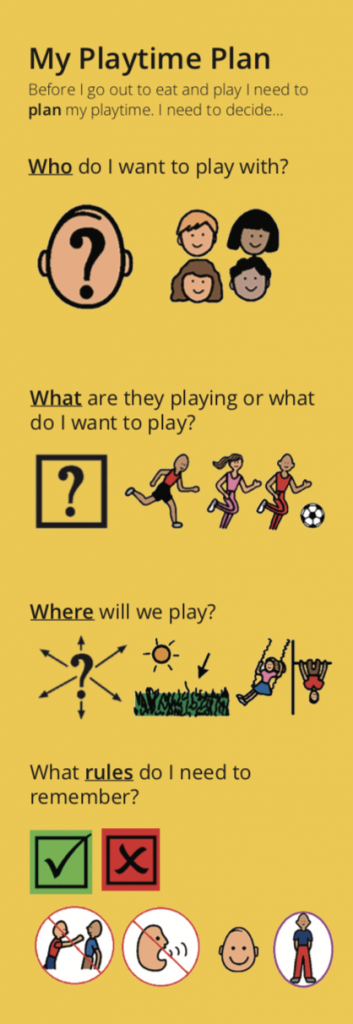

- A visual prompt such as below

WHAT MIGHT EXPLICIT TEACHING OF A SPECIFIC FRIENDSHIP SKILL LOOK LIKE?

Here’s an example of what a child’s playtime plan could look like:

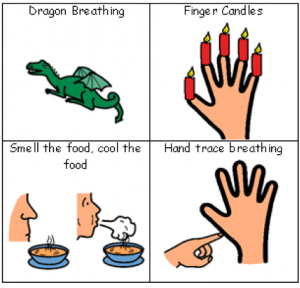

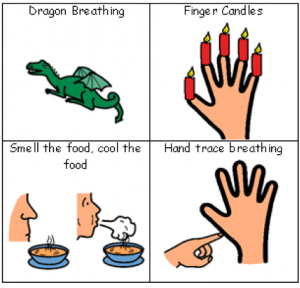

When a child is feeling anxious or angry, feelings will overtake thinking. So, for children to engage socially with others, we need to first help them regulate their own emotions. This begins with emotional literacy. Teaching children that feelings are OK. We all have feelings. Sometimes these feelings are big – a lot of anger. Sometimes these feelings are small – a little bit angry. Feelings do change – in the same way that clouds move across the sky. However, we can be in control of our feelings. Our feelings don’t have to control us. We can help our feelings to move – in the same way that the wind moves the clouds.

We can teach children breathing tools, body tools and brain tools.

BREATHING TOOLS MIGHT BE

BODY TOOLS MIGHT BE

BRAIN TOOLS MIGHT BE

Author, Dr Susan Lowe is the Owner and Principal Occupational Therapist at Skills for Kids in Penrith, NSW where occupational therapists and speech language pathologists provide assessment and intervention services for children and teens. In relation to this article, the therapists teach children 1:1 during school terms and in Playground Skills group programmes during school holidays how to regulate their emotions and how to interact socially with friends. Thanks to Dr Julianne Challita, Senior Occupational Therapist for contributing to this article.

For more information, visit the website www.skillsforkids.com.au OR contact 02 47390267.